JSON, specified by RFC7159 has taken over from XML as data format of choice for web service APIs. Developers like how JSON is less verbose and easier to use than XML, but its limitations lead to extra work for some applications.

JSON defines a small number of types: objects, arrays, numbers and strings, as well as three special values - true, false and null.

However, JSON does not include a mechanism for defining custom domain types.

Fortunately, there are several options to choose between, all bad.

This blog post compares their disadvantages, so you can choose the least bad for your situation.

1. No type information

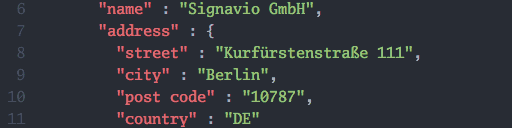

Consider this example of an invoice for some Signavio merchandise. The default way to serialise something like an invoice to JSON is not to include any type information.

{

"created" : "2016-24-11",

"due" : "2016-24-12",

"number" : 42,

"supplier" : {

"name" : "Signavio GmbH",

"address" : {

"street" : "Kurfürstenstraße 111",

"city" : "Berlin",

"post code" : "10787",

"country" : "DE"

},

"telephone" : "+493085621540",

"VAT number" : "DE265675123"

},

"fees" : [

{

"description" : "Signavio t-shirt (S)",

"quantity" : 20,

"price" : {

"currency" : "EUR",

"amount" : 10.00

}

},

{

"description" : "Signavio t-shirt (M)",

"quantity" : 30,

"price" : {

"currency" : "EUR",

"amount" : 10.00

}

}

],

"total" : {

"currency" : "EUR",

"amount" : 500.00

}

}

In this ‘normal JSON’, the types are implicit. This includes a number of JSON objects and values of different types.

| Object | Type |

|---|---|

| (root) | Invoice |

| created | Date |

| supplier | Organisation |

| address | Street address |

| post code | German post code |

| telephone | E.164 telephone number |

| VAT number | European Union VAT identification number |

| fees | list of Invoice Line |

| description | Product description |

| quantity | Product quantity |

| price | Money |

| total | Money |

If you publish an API that uses this kind of JSON then you will also have to publish API documentation that defines these types so that developers know which kinds of data are used, and where, and what the data means. We used to call that a data dictionary.

Modules that serialise and deserialise this JSON either share definitions of these types, or they are not ‘type aware’ and cannot perform any validation. Shared type definitions might be Java domain model classes, usually POJOs, used with a JSON library such as Jackson.

The alternative approach processes JSON without a static data model. Pascal Voitot a.k.a. mandubian originally described this approach in his blog post, From Data-Centric Approach to JSON Coast-to-Coast Design With Play-2.1 & ReactiveMongo - a long but worthwhile read.

For data validation, you can compromise by writing domain validation rules that check the JSON representation directly. For example, instead of modeling an E.164 telephone number using a Java class, you could instead write code that checks the JSON string value when deserialising the JSON representation.

Either way, either approach to using JSON that does not contain type information results in external assumptions about which types are present in the JSON structure. The next thing to try is making the type explicit.

2. Inline type property

For the next step you can specify each JSON object’s type in a special inline property.

You can probably avoid name clashes by using an underscore prefix, calling it _type.

{

"price" : {

"_type" : "Money",

"currency" : "EUR",

"amount" : 10.00

}

}

This approach makes parsing inconvenient, because the type property could appear anywhere among the other properties: you only know which properties you expect after you’ve read the type property. The parser will have to parse the whole object in order to discover the type, before it can then parse and validate the object according to its type.

In practice, you’ll also find this inconvenient because your serialisation code will now have to handle the type separately from the other properties.

3. Type and value properties

You can keep your serialisation code relatively clean by separating the object’s type information from its value. This also allows the parser to read the type before reading the value using a type-specific parser.

{

"price" : {

"type" : "Money",

"value" : {

"currency" : "EUR",

"amount" : 10.00

}

}

}

However, you now have an extra level of nesting in your object, and two extra properties, which reduce readability.

4. Type name and value as array (tuple)

Instead of using the type and value name as a property name and object value, you can use an array.

In this approach, the array holds the same pair of values as the object in the previous approach, but transforms the type and value properties to anonymous array items.

{

"price" : [

"@Money",

{

"currency" : "EUR",

"amount" : 10.00

}

]

}

This probably only makes sense if you use a programming language with tuples, and you’re used to pairs of values. Otherwise, the array looks like a mixed-type list of values, where you just have to know which is which because they don’t have names. This may confuse people.

5. Type name and value as object property

You can separate the type name and object value more neatly by using the type name as the property name.

This example uses a @ prefix for the type name, to make the JSON more human-readable.

{

"price" : {

"@Money" : {

"currency" : "EUR",

"amount" : 10.00

}

}

}

However, the JSON still has another level of nesting, albeit with less fluff.

6. Multiple type properties

You can extend the previous approach by mixing multiple types, so you can represent object inheritance.

This example represents the same model, with the addition that Money subclasses (extends) Number.

{

"price" : {

"@Number" : {

"amount" : 10.00

},

"@Money" : {

"currency" : "EUR"

}

}

}

This approach gives you the advantage that common (shared) properties have a predictable path, such as @Number.amount, that you can use in expressions.

However, the JSON is even more verbose and having the types in random order would reduce readability.

This approach also supports multiple inheritance, but you’ll have to decide for yourself whether you think that’s an advantage or disadvantage.

Schema definitions

All of the above approaches refer to types by name. This means that you have to define the data types elsewhere, perhaps as a class model in an object-oriented programming language, using some API or in a declarative format.

You might also consider options for JSON-centric data model definitions, that you can use to define types like Money:

- JSON schema - a JSON representation of type definitions that you use in JSON documents, with a similar focus to XML Schema.

- GraphQL - a query language for JSON APIs that includes a type system and schema language for defining the data in queries and JSON documents.

You can use both JSON Schema and GraphQL to specify and validate the structure and data in your JSON documents. To start with, you might not think you need this, but sooner or later, you’ll wish you had a single definition of your data model and JSON serialisation format.